Suvarnabhumi

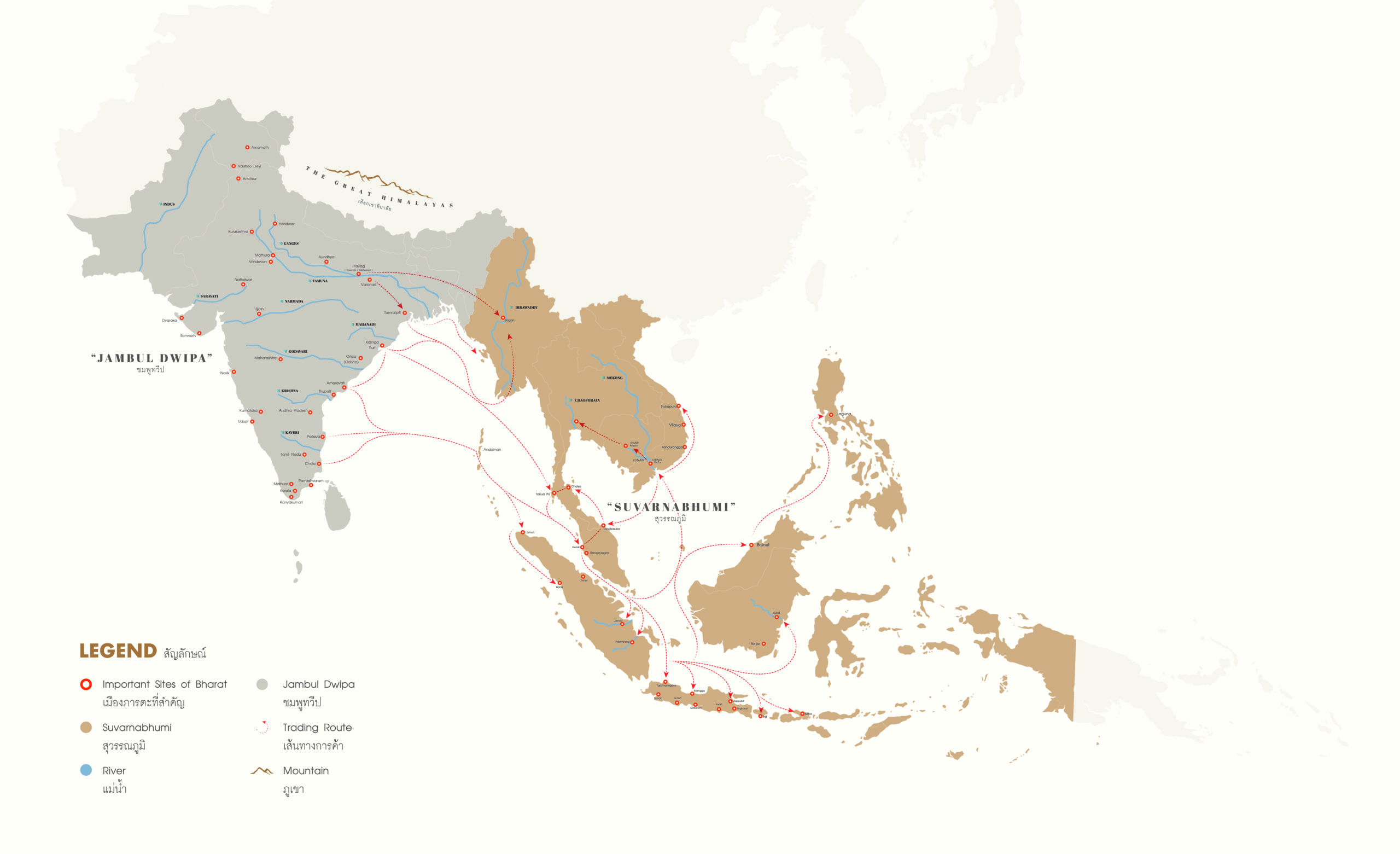

Suvarnabhumi, or “The Golden Land,” does not refer to a territory literally rich in gold. It signifies a land of opportunity that records the historical and cultural journeys of humankind. It evokes the maritime trade routes that linked major port cities and served as points of convergence for diverse civilizations.

This collection invites us to reconsider the idea of “Suvarnabhumi” through the shared roots and cultural exchanges carried along these sea routes. It offers a perspective that moves beyond the conventional notion of a land of gold and guides us toward the deeper foundations of Southeast Asian civilization. This is a civilization shaped over millennia by spiritual beliefs and sacred epics, beginning with the arrival of merchants from the Indian subcontinent who brought the stories of the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata into the region.

This is an intellectual journey toward understanding how ideals of kingship and dharma evolved into a form of cultural DNA that continues to shape the identity of the peoples of Suvarnabhumi. It encourages us to reflect on our cultural heritage with renewed clarity in the contemporary world.

“Suvarnabhumi,” in this collection, becomes the key that unlocks the enduring mysteries of the Golden Land.

Masks of Faith: Living Cultural Heritage in Asia

Ramayana Masks: The Shared Epic of Asia

India, Sri Lanka, and the Himalayas

Human civilization first flourished along four great rivers: the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia, the Nile in Egypt, the Huang He in China, and the Indus in India. Among these, the Indus Valley gave rise to one of the world’s earliest and most enduring cultures on the Indian subcontinent, a land long known as Bhāratavarṣa, or “the land of Bharata.”

The name India itself comes from the Indus River. When the Persian and Greek empires entered this region, they called its people Sindhu or Hindu. During the era of Alexander the Great, Greek armies reached the Indus River, and many settled along its fertile banks. The Greeks pronounced the river Indos, a name that later evolved into Indus and eventually India.

The people of this land, however, have always called their homeland Bhāratavarṣa, believing themselves to be descendants of King Bharata, the noble ruler in the epic Mahābhārata. This ancient text is regarded as part of the sacred Vedic tradition.

For more than five millennia, most of the subcontinent’s inhabitants have followed the Brahmanic or Hindu faith. Devotees believe that their religion has neither beginning nor end, but exists as an eternal truth alongside the world itself.

When the Aryans migrated into the Indus Valley and displaced the earlier Dravidian peoples, they established their belief system under the name Sanātana Dharma, meaning “the eternal law of nature.” Over time, this faith came to be known as Hinduism. Its central trinity, the Trimūrti, unites three divine aspects: Brahma the Creator, Shiva the Destroyer, and Vishnu the Preserver.

Throughout Southeast Asia, every region absorbed and developed their own Ramayana tradition. It reflects how beautifully each culture enriched in silence and art. The festival “Songkran” came earlier in Eastern states of India, then had its flowing and celebration into “Makara Poornima Boita Bandana” where water celebrated during similar performance days. They followed the lunar and solar calendar.

Ramayana Masks: The Shared Epic of Asia

People in India still tell and perform the Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa without interruption. These timeless epics continue to inspire diverse forms of performance across regions and communities, each shaped by local customs and interpretations that weave together devotion and creativity.

In the world of art, countless paintings and sculptures portray the life of Rāma. One sculpture, now housed in a museum in Delhi, depicts Bharata carrying Rāma’s sandals upon his head. Others represent Rāma, Lakṣmaṇa, and Sītā in the refined style of South Indian art.

At the Papanaṭa Temple in Pattadakal, sculpted reliefs narrate the Rāmāyaṇa from beginning to end, while the caves of Ellora feature murals of the Mahābhārata on one side and the Rāmāyaṇa on the other. In Vijayanagara, depictions of Hanuman mark the early origins of his worship. Masked performances are also found in many regions such as Rajbanshi and Sikkim, showing how mythology endures through art and ritual.

The variety of faiths and beliefs in India has given rise to many traditions of masked performance, each expressing spiritual ideas in its own way. In the highlands where Mahāyāna Buddhism flourishes, such as Bhutan with its Vajrayāna and Tantric influences, performances often reflect spiritual transformation and symbolic devotion. India’s artistic and religious heritage has also extended to neighboring Himalayan countries including Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, where masks remain integral to rituals and expressions of belief.

In northern India and the Himalayas, especially in Rajbansi, Tharu, and Sikkim, masks of the goddess Kālī are worn for protection, while masks of Hanuman symbolize devotion and courage. Wooden masks of Varāha and Rāvaṇa, carved with ten aligned heads, echo the imagery seen in epic reenactments and modern adaptations of the Rāmāyaṇa.

Nepal preserves its ancient animistic traditions through masks such as Lakhe, the male demon, and the Goiter female mask. In West Bengal, the Purulia Chhau dance employs intricately crafted masks to dramatize stories from the Indian epics as part of rituals linked to the hunting festival. In Odisha, the Sahi Yatra is a grand street performance featuring hundreds of participants. It commonly stages the Rāmāyaṇa or Prahlada Nataka, recounting the tale of Narasiṃha, one of Viṣṇu’s ten avatars who vanquishes evil. The Seraikela Chhau of Bihar, conceived by a royal prince for the annual Chaitra Parva agricultural festival, presents masks of deities such as Krishna, Shiva, Chandra, and the Sun God.

Sri Lanka preserves two prominent mask traditions, Yakun and Kolam. Yakun centers on the demon Sanni, believed to cause illness, and is performed in exorcism rituals. The Kolam Natima employs masks in ceremonies meant to protect pregnant women and infants from malevolent spirits, uniting healing with sacred performance.

In Tibet, the masked dance Cham has its roots in the pre-Buddhist Bon religion, which emphasizes spirit possession and the expulsion of evil. The performers, often shamans or village leaders, wear masks such as Citipati and Mahākāla. When Tibetans later embraced Vajrayāna Buddhism and Tantric practice, these masks evolved into representations of Bodhisattvas, Dharmapālas, and enlightened masters who protect the Dharma. Another theatrical form, Lhamo, uses masks to portray historical legends, heroic deeds, and episodes from the life of the Buddha. These performances continue to serve as religious dramas that teach moral and spiritual wisdom.